Of all the tools we have for valuing the stock market, the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio (CAPE) and the equity q ratio are the most credible, with long histories and sound theory behind them. And right now, these suggest that the S&P500 is around 40% overvalued.

This isn’t quite as expensive as the market was in 2000, but it’s up there with other peak valuations over the past century. What’s more, stocks haven’t been consistently cheap for almost two decades, according to the same metrics. Even during the worst of the 2008-2009 panic, the market only briefly dipped below fair value.

That stands in sharp contrast to the usual stockbroker chatter that equities are cheap, but there’s no question which verdict investors should take more seriously. However, the degree and persistence of this overvaluation certainly raises some questions.

Few investors who look at CAPE and equity q seemed to have considered whether these measures could be giving us the wrong signals. But if you dig into the details, it seems very plausible that they could be making the S&P500 look more expensive than it is – although it’s still difficult to conclude that US stocks are cheap.

Stockbroker economics at its most misleading

(NB: The first part of this article reviews different methods of valuing stockmarkets and explains why we need CAPE and equity q – readers who are already familiar with this may wish to jump ahead one or two sections.)

Stockbrokers like to value markets using the price/earnings ratio based on forecast earnings, because it’s easy to grasp. Every investor understands the p/e ratio. A cynic would also say that they like it because it’s usually possible to make the market seem cheap on this measure.

For example, right now, you’ll read that the S&P500 is on a forecast p/e of around 11.5, compared with a long run average p/e of about 16.5. That makes it look great value.

However, there are two major problems. First, you can be optimistic with those earnings forecasts – and analysts are consistently too optimistic about earnings growth.

Second, it’s almost ubiquitous to compare the p/e based on forecast earnings (11.5 above) with the long-run average p/e based on reported earnings (16.5 above). This is completely misleading, because forecast p/e ratios are generally lower than trailing p/e ratios. By picking the wrong long-term average, you’re immediately making the market look artificially cheaper.

But even where analysts are not playing fast and loose with the figures, the p/e is a flawed measure. The snag is that the ‘right’ p/e ratio depends on where in the cycle you stand.

A low-looking p/e based on peak earnings might still mean the market is more expensive than a high p/e based on earnings at the trough or a recession. And calling the cycle is extremely difficult.

The dividend yield is equally troublesome, because dividends also rise and fall through the cycle. In addition, dividend policies have changed over time – for example, firms have chosen to increase share buybacks instead of increasing dividends – making it hard to compare dividend yields to long-run trends.

The price/book ratio is a less flawed metric, since book value usually does not swing so dramatically through the cycle. But it still has issues: p/b depends on the book value of corporate assets being their real present economic value, hence there are potential errors due to misreporting, inflation and changes in the trend return on equity over time.

However, as long as investors bear these limitations in mind, p/b is the soundest of the three and can be useful in valuing markets. For example, it has a pretty good track record when it comes to assessing likely returns for Asia ex Japan.

Notably, very few stockbrokers seem to use market p/b in their valuation work. That may have something to do with the fact that the numbers are harder to fiddle to get the upbeat answers they prefer.

Understanding CAPE and equity q

While p/b is useful, something even more robust would be better, which leads us to the alternative valuation metrics that attempt to solve all these problems. These are the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio (or CAPE), popularised by Robert Shiller, and equity q (or the q ratio), based on work by James Tobin and developed into its current form by Andrew Smithers and Stephen Wright.

There’s not enough space here to go into full details of the reasoning behind either CAPE or equity q. For a comprehensive explanation, see either Smithers and Wright’s Valuing Wall Street or Smithers’ updated Wall Street Revalued. (Shiller’s Irrational Exuberance is worth reading as well, but the others are more informative.)

Briefly put, CAPE tries to remove the uncertainty that the economic cycle brings to the p/e ratio by using a 10-year inflation-adjusted average of earnings instead of immediate past earnings or forecast earnings. Equity q compares the stock market value of equities to their replacement cost, on the basis that markets are undervalued when the shares trade at less than the replacement cost of the underlying assets and vice versa (equity q is very similar to the price/book ratio, but it uses what should be the current economic value of the underlying assets, rather than their adjusted historical cost).

The only market for which there are very long-term data sets for CAPE and equity q is the S&P500. We can calculate a respectable amount of CAPE data for some other developed markets, but the long-term data to calculate equity q doesn’t exist for countries other than the US.

Despite this limitation, the two measures are extremely useful for assessing the S&P500, which remains the world’s most important equity index. They give similar results (as they should – if the cyclical adjustment is perfect, they are theoretically equivalent measures) and have been a good predictor of long-term returns over the past century. When they were low, it was a good time to buy and when they were high, it paid to be out of the market.

(The chart above is available on the Smithers & Co website and is updated quarterly.)

So equity q and CAPE have enough of a track record to be worth taking seriously. And currently both measures say the S&P500 is around 40% overvalued. That’s not as bad as in 2000, but it’s still among the highest valuations on record and suggests US stocks are extremely expensive by historical standards.

Note that this doesn’t have to mean a crash is imminent. A high valuation simply says that from this point, long-term returns are likely to be below par. And there are possible explanations for this than don’t involve equities simply being in a bubble.

It could be that investors are happy to accept these lower returns than they were decades ago, because equities have become less risky. Demographic may play a part: a surplus of middle-aged savers relative to the supply of equities might have pushed equity prices up.

But whatever the reason, stocks appear expensive. That would suggest that unless valuations rise even higher (and the trend since 2000 seems to have been in the opposite direction), disappointment is likely when buying at these levels.

All this seems pretty clearcut given the track record of CAPE and equity q. But what if something has changed and they are now giving us a misleading picture of the degree of overvaluation?

The tricky question of intangibles

There’s no doubt that CAPE and equity q are theoretically sound as valuation measures. But that doesn’t necessarily make them immune to data issues.

One telling anomaly with equity q is that over time equity q should average 1, this being the point at which the market value of shares and the replacement cost of assets is equal. In practice this isn’t the case.

According to Smithers and Wright’s data, the long-term average value of equity q is 0.63. For the most part, they explain this by claiming that the replacement cost of company assets is generally overstated since depreciation is underestimated.

This makes sense and seems consistent with the accounting policies followed by many CEOs (maximise reported revenue, minimise reported costs and make reported profits look as good as possible). And it’s not a problem by itself.

The only consequence is that one can’t simply take equity q and assess stocks as overvalued if the measure is over 1 and under valued if the measure is under 1. Instead one needs to compare it to that long run average of 0.63.

But doing this assumes that any discrepancies in the reported replacement costs of assets are constant over time. If that isn’t the case, the equity q figure from today may not be measuring exactly the same thing as the equity q figure from decades ago – and so the comparison between today’s figure and the historical average may be misleading.

How might the discrepancies creep in? Companies have both tangible assets and intangible ones; in general, the value of intangible assets such as brand ownership and patents is not well captured by standard accounting methods and may not be fully represented on the balance sheet. As a result, the replacement cost of assets may not fully reflect the value of these intangibles.

As long as the proportion of intangible to tangible assets remains constant, this is not a problem. Assume the stock market is worth 500, reported assets are 900 and unreported intangibles are another 100. Then equity q based on reported numbers is 500/900=0.56 and equity q based on all assets would be 500/1,000=0.5.

Then assume the stock market is later worth 1,000, reported assets are 1,800 and unreported intangibles are another 200. All proportions and ratios then remain the same; equity q based on reported assets is still 0.56 and equity q based on all assets is still 0.5.

But now assume that the proportion of intangible assets rises from 10% to 20%. Then the stock market is worth

1,000, reported assets are worth 1,600 and unreported intangible assets are worth 400. At that point, equity q based on reported assets is 0.625 and the market looks much more expensive. But equity q based on all assets is still 0.5.

Thus all else being equal, if you increase the proportion of unreported intangible assets, equity q will appear to drift upwards. Crucially, the same will happen for CAPE; since intangibles are generally expensed immediately rather than depreciated, reported earnings will be lower and CAPE will appear to be higher, even though investors are ultimately paying the same price for the same underlying returns.

Is the share of intangibles growing?

This theoretical glitch is only a problem if the share of corporate expenditure and corporate assets that involve intangibles are changing over time; if intangibles are constant, equity q is not affected (despite the claims of some critics). Unfortunately, there is some evidence that this is happening.

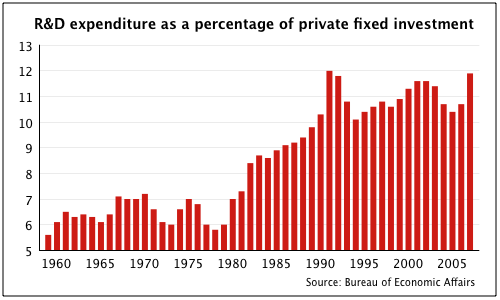

In a research note from last year, John Higgins of Capital Economics points out that the US Bureau of Economic Affairs data shows private business expenditure on research and development (ie intangibles-generating expenditure) has increased from 5.6% of private fixed investment in 1959 to 11.9% in 2007. R&D expenditure is often riskier than expenditure on tangible assets and some of this may turn out to be worthless. But even with that in mind, it seems likely that the influence of intangible assets on the underlying net worth and earnings of firms has grown.

(Note that 2007 is the most recent date for which this is available – the series is an experimental BEA one rather than a standard dataset. See this 2010 paper for more details [PDF]. The chart above includes a small amount of double-counting of R&D software expenditure which can’t easily be stripped out for the whole series with the public data the BEA has provided.)

Still expensive – but perhaps less expensive

There are other possibilities that would also bias historical comparisons. For example, if the extent of underreporting of depreciation has changed over time, that would also mean that comparing equity q and CAPE across time becomes harder. (If depreciation were more accurately recorded today, that would justify a higher CAPE and a higher equity q relative to the long-run average because investors would need to make a smaller implicit allowance for the depreciation that isn’t being reported.)

We can also speculate about changes to the composition of the market, changes to the tax system and other factors. Weighing all this, it’s easy to suspect that the S&P500 may be significantly less overvalued today than it appears to be relative to long-term trends in CAPE and equity q.

However, proving the effects of this is difficult. Adjusting for it is even more so. Obviously, the shorter the historical period you look at for comparison, the less likely it is that your ratios are being affected by major shifts in the nature of the underlying data. But ideally you want to use as much original data as possible; otherwise, you risk drawing conclusions from a history that is too short or too biased to be valid.

For what it’s worth, just looking at CAPE and equity q since 1959 – ie the start of the period over which we can track the rise in R&D spending above – gives a slightly different result. Both metrics suggest the S&P500 is around 20-25% overvalued, rather than 40% on the longer-term figures.

That gives us a slightly different take on recent history. For example, it suggests that at the peak of the crisis in March 2009 when the S&P500 briefly plunged to around 670, it may have been around 30-40% undervalued, rather than a little below fair value. That seems more consistent with what you’d expect during such an extensive panic.

And it suggests that the S&P500 might be fair value at around 1,050. Long-term averages for equity q and CAPE suggest that it would need to fall much further, to around 900, before the overvaluation disappears.

Clearly, the market today still seems to be significantly overvalued. And even with the most generous assumptions on how equity q and CAPE could be distorted, it’s hard to see how the S&P500 could actually be undervalued at present. There is no sign this is an outstanding time to buy.

However, investors who are trusting these metrics to identify when US equities will finally be good value again need to consider whether our current assumptions may be too pessimistic. Equity q and CAPE may never again look as clearly cheap as their history is leading us to expect.