World Hyperinflations, a recent working paper by Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus, is exactly what the title would suggest: An attempt to collect data on every hyperinflation on record. They count 56, possibly 57, and Hanke has since suggested that Iran is on the way to becoming number 58.

You might assume that these events are already well documented, but there have been few serious studies, despite the popularity of the topic. To quote the paper:

The literature on hyperinflation is replete with ad-hoc definitions, vague, ill-defined terminology, and a lack of concern for clear, uniform metrics. In consequence, sloppy reasoning is all too common. Although Peter Bernholz (2003) has provided the most comprehensive list of hyperinflation episodes available (30 cases), he does not follow a precise, consistent definition, and misses almost half of the cases we report in this chapter. Without a complete list of hyperinflation episodes in the scholarly literature, many people simply rely on Wikipedia and the unreliable information contained therein (e.g. Fischer 2010). To fill the void in the academic literature, we set out to construct a new, comprehensive table of the world’s hyperinflation episodes.

The paper is worth reading (it’s very short) and the point that jumps out of the main list (on page 13) is that hyperinflations have not happened in even vaguely normal economies – they’ve been associated with extreme conditions (such as war and its aftermath or radical restructuring of an economy). That’s exactly as you’d expect.

Adam Fergusson’s When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Hyperinflation – which analyses the early 1920s hyperinflations in Austria and Hungary as well as the more famous Weimar episode – demonstrates this extremely well. (Also worth a look is Liquat Ahamed’s Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, which covers the hyperinflation in less depth, but adds a great deal of insight on the wider 1920s and 1930s monetary environment).

Could hyperinflation happen today?

Some may see this as evidence that current central bank policies will not lead to hyperinflation – and if you look at the context for some of the episodes in the Hanke and Krus data, it’s hard to see how anything similar happens in an economy that isn’t already in crisis. But it’s worth bearing in mind that the paper uses a very specific definition of hyperinflation: The inflation rate must top 50% per month.

That makes sense, since every study needs a cut-off point. But it means that these conclusions apply only to a very limited number of events – there are plenty of countries that have experienced very painful episodes of high inflation that fall short of 50% per month.

Some fall under the same category as the ones in the paper: Japan after World War II would be an example – in terms of the underlying dynamics, it’s hard to separate this from events in other countries at the same time that make the list.

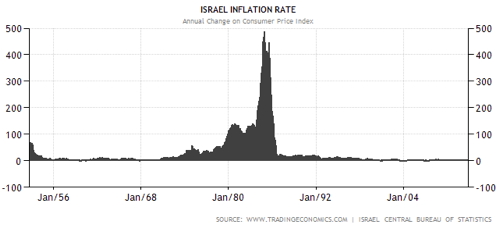

Others are rather different. Perhaps most famously, Israel saw inflation begin to rise in the 1970s along with most of the industrialised world; however, Israeli inflation went higher and lasted for longer, peaking at a yearly rate of 486% in November 1984.

Unlike the episodes of hyperinflation, this wasn’t the result of a complete breakdown of the economy. Instead, it seems that a culture of indexing prices and wages to inflation became deeply entrenched, creating an inexorable wage-price spiral.

One of the very relevant lessons in Fergusson’s When Money Dies is that policymakers permit inflation to get out of hand because stopping it has such a serious impact on unemployment and wages that it seems to be the least worst option in the short term. It also has the benefit of erasing the government’s domestic debt in real terms.

Allowing that to balloon into hyperinflation requires a complete breakdown of the system, but opting for high inflation is rather more common – as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff show in their paper The Forgotten History of Domestic Debt and the more detailed This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. While the Hanke and Krus data suggests that we can rule out hyperinflation in practically all circumstances, it’s less clear that high inflation is out of the question.